A Museum Within A Museum

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Diana Paterno, Collections Management Intern

September 28, 2023

While interning in the Collections and Exhibitions Departments this past Spring, I was granted the opportunity to work on a grouping of artifacts in preparation of the “Corner of Curiosities,” a forthcoming display area containing artifacts from the Museum’s permanent collection that are unique in their subjects and small size.

I was responsible for updating the collections database for nearly 60 artifacts, including photographing, taking dimensions, condition reporting, and researching each one of them. The work was time consuming, but proved very rewarding. Additionally, I was able to put my previous art conservation experience to good use in a museum setting, where I was tasked to take care of a public collection, something I’ve always yearned for.

So, allow me to take you on a journey where I introduce you to the history of cabinets of curiosity that inspired this upcoming display, and a few of my favorite items in the Museum’s modern corner of curiosities.

Cabinets of curiosities are a centuries old practice beginning in Europe during the Renaissance. “Kunst-und wunderkammern” translates to “cabinets of art and marvels,” is often shortened to “wunderkammer,” meaning “room (or cabinet) of wonder,” or “kunstkammer,” meaning “chamber of art.”

These mini-museums were an early predecessor to the modern form. They were held by private collectors, who specialized in collecting rare, obscure, and strange objects.

Left: Ritratto del Museo di Ferrante Imperato. [Double plate showing the interior of Imperato’s museum and library.] 1599. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library S16 O40.

These cabinets functioned as conversation pieces, and showed how wealthy, knowledgeable, and traveled the host or collector was, as collections were built piece by piece as the collector journeyed around. Don’t be fooled by the use of the word cabinet, these collections ranged in size from a few shelves to a whole room.

There are four main types of artifacts typically found in these collections: artificialia, which are man-made objects including antiques, and works of art; naturalia, which are animal specimens, creatures, and “monsters;” exotica, which are exotic animals and plants; and scientifica, which included scientific instruments. These cabinets even sparked interest in early scientists and have greatly contributed to the foundation of modern medicine. In the 19th century, focus shifted from cabinets of curiosity to private art collections and public art institutions. While there are many kunst-und wunderkammern still in existence there is a certain benevolence in allowing the public to experience all of these once privatized wonders.

The Seaport Museum is transforming this traditional practice into a new space with a modern twist. The “Corner of Curiosities” will showcase rare and small scale objects in the collection, out of the traditional cramped cabinet space and into a well lit and organized display. These items have rarely been displayed for the public, and contain mostly artificialia curios, interwoven with the occasional scientifica instruments.

With that said I would like to introduce a few of my favorite objects that I’ve worked with!

Ivory Diptych Compass and Sundial (1625)

This ivory compass and sundial is easily among one of the most beautiful items in the Museum’s collections. Nestled deep in storage, this small folding diptych tells the story of how we told time and circumnavigated the globe before the use of modern cartography and clocks.

Hans Tröschel the Younger (German, probably born 1599, died before 1634) was a compass maker from Nürnberg Germany whose specialty was in making portable navigation and timekeeping devices, usually from wood or ivory, in the late 16th and early 17th century. We know that this object can be attributed to Hans Tröschel the Younger because the diptych is marked with his authorship mark, a six pointed star. Additionally, the piece is dated 1625, when Tröschel the Younger’s predecessor Hans Tröschel II, who’s maker’s mark depicts a bird on a twig, already passed away.

This compass and sundial has many elements that made it truly advanced for its time. It comes complete with a magnetic compass, a hand dial compass chart listing eight cities with their general N,S,E,W cardinal directions and latitudes on the top lid.

A string gnomon sundial with two dials to give the most accurate time reading, an equinoctial hour chart, and a winter solstice chart with zodiac symbols to indicate the seasons sits inside the interior panels. A lunar volvelle (for interconverting solar and lunar times), and lists of great cities and their latitudes adorn the bottom lid, as well as various other measuring and calculation tools.

Latin inscriptions engraved on the panels announce: “Perge/ Secvrvs/ Monstro/ Viam”, “Qvantitas Diet/ Planetarvm Horas/ Hora Fvit Mors Venit/ Horologium Aeqvinotiale”, “Horae Ab Meridie/ Solsticivm Hiemale/ Solsticivm Estavvm/ Horae Ab Ortv Et Occasv”, and “Dies Aeta/ Tis Lvne/ Et Horae/ Noctis”.

While some of these have unclear translations, certain ones aided me in discovering what was being depicted on the clock, for example “Horologium Aeqvinotiale” translates to equinoctial clock and “Solsticivm Hiemale” means Winter solstice.

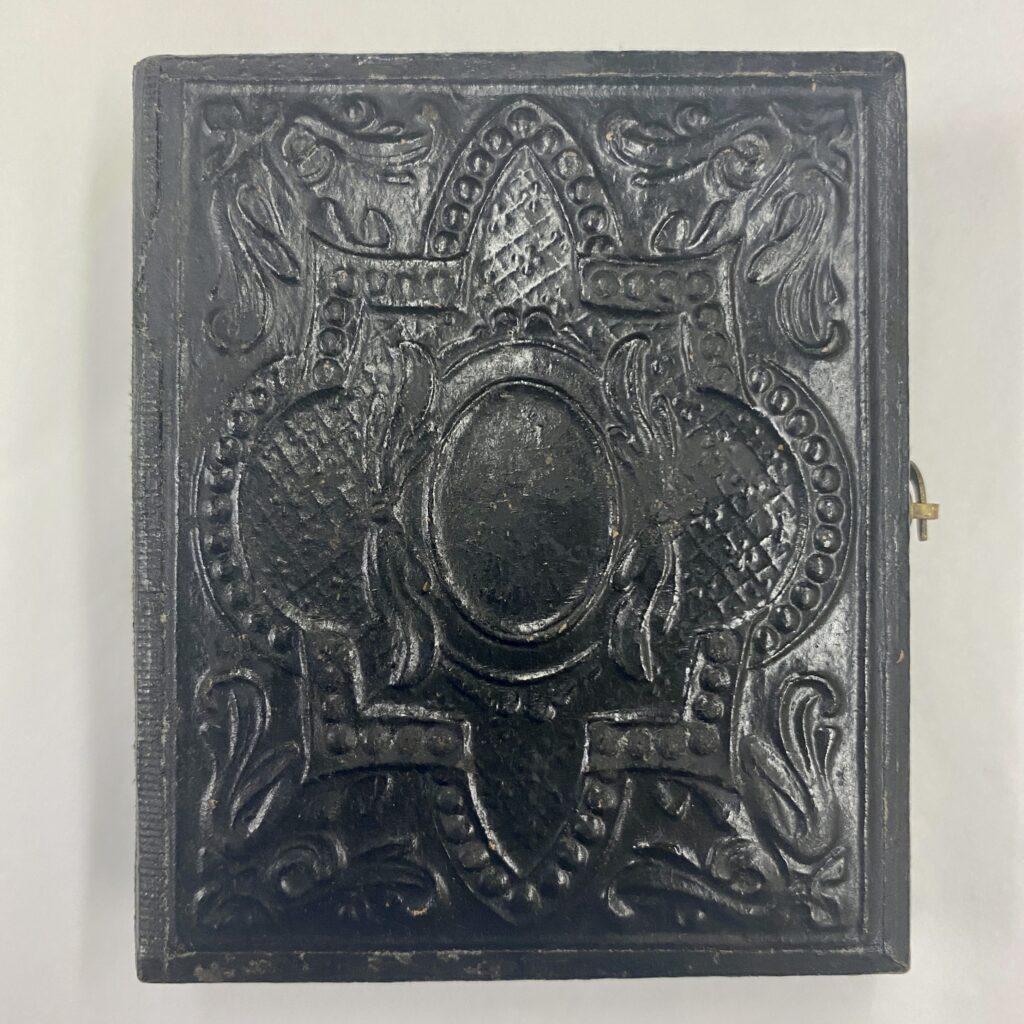

Daguerreotype of a Young Man (ca. 1839–1860)

The beauty of Daguerreotypes is that the exact image you see can only be produced once. Daguerreotypes mark the beginning of photographic history as we know it, and I was able to hold this historic medium in my hands.

In the 19th century, there was a great expansion of information, as news traveled faster than ever the need for accompanying depictions followed.

The Daguerreotype was introduced in France in the summer of 1839 by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851). This first of its kind art involved taking a polished silver coated copper plate and allowing it to sensitize in a lightbox with iodine and bromine vapors, after being transferred to the camera, the image was developed, toned, and stabilized to prevent further light exposure.

The exposure time for this new process was only 20 minutes, this exciting invention meant a boom in photography followed in the mid-1800s. However, this new art was not accessible to everyone, the cost for a daguerreotype could cost up to $5 (in the mid-1800s that was almost one week’s worth of wages for the average day laborer!) By 1850, there were over 70 daguerreotype studios in New York City.

In this daguerreotype we can see a well dressed young boy looking into the camera, he is seated holding his straw hat in his lap, with a backdrop of the sea with sailing vessels behind him.

While the Museum does not possess any information about the sitter’s identity one can only assume that he came from well to do circumstances, as he is young, well dressed, and sitting for an individual portrait, not a group shot or a commemorative photo.

The elaborate case that encapsulates this image is a rarity not often seen in today’s photographic age. The hand carved wood exterior, red velvet with floral motifs, and gold frame pieces remind us of how rare the experience of getting your image taken was before the modern age.

Daguerreotypes fell out of fashion quickly in the late-1850s when the Ambrotype, a less expensive and faster photographic process was developed, making the surviving daguerreotypes prompt us to appreciate this truly fascinating moment in history.

Spinning Jenny (ca. 1803–1815)

The delicate handiwork of this carved bone spinning jenny automaton was actually carved by a prisoner of war from the Napoleonic Wars between 1803 and 1815, when Britain declared war on Napoleon-ruled France.

This was the first large-scale application of mass conscription, otherwise known as the draft. Many of the men drafted to serve in the war came from non combative backgrounds, including the arts and various trades. Before the French Revolution, it was customary to exchange prisoners between fighting parties. Napoleon stopped this practice, believing that any able-bodied men posed a threat to the French.

Prisoners of war were therefore held indefinitely on both fighting sides, these crafts and trades evolved as a way of entertaining themselves and producing a good that could be traded or sold for something more useful, such as threads, metal, tools and more at “fairs” held during their imprisonment. The prisoners got their materials from beef bones in their soup rations.

The spinning jenny machine was an early hand powered multi spindle machine created by James Hargreaves, an English inventor, and patented in 1764. This machine was a significant factor of industrialization in the textile industry. It allowed cotton to be spun into 8 threads at once, which was significantly faster than spinning one at a time by hand.

This piece depicts a woman, wearing a yellow and red dress and white bonnet, sitting at a spinning jenny machine. The worker “spins” the string through the jenny when the low front facing wheel is turned. Her hand moves back and forth when the string is “spun.” While we may never know the artist behind this automaton, we can appreciate the history of its creation (no matter how unfortunate).

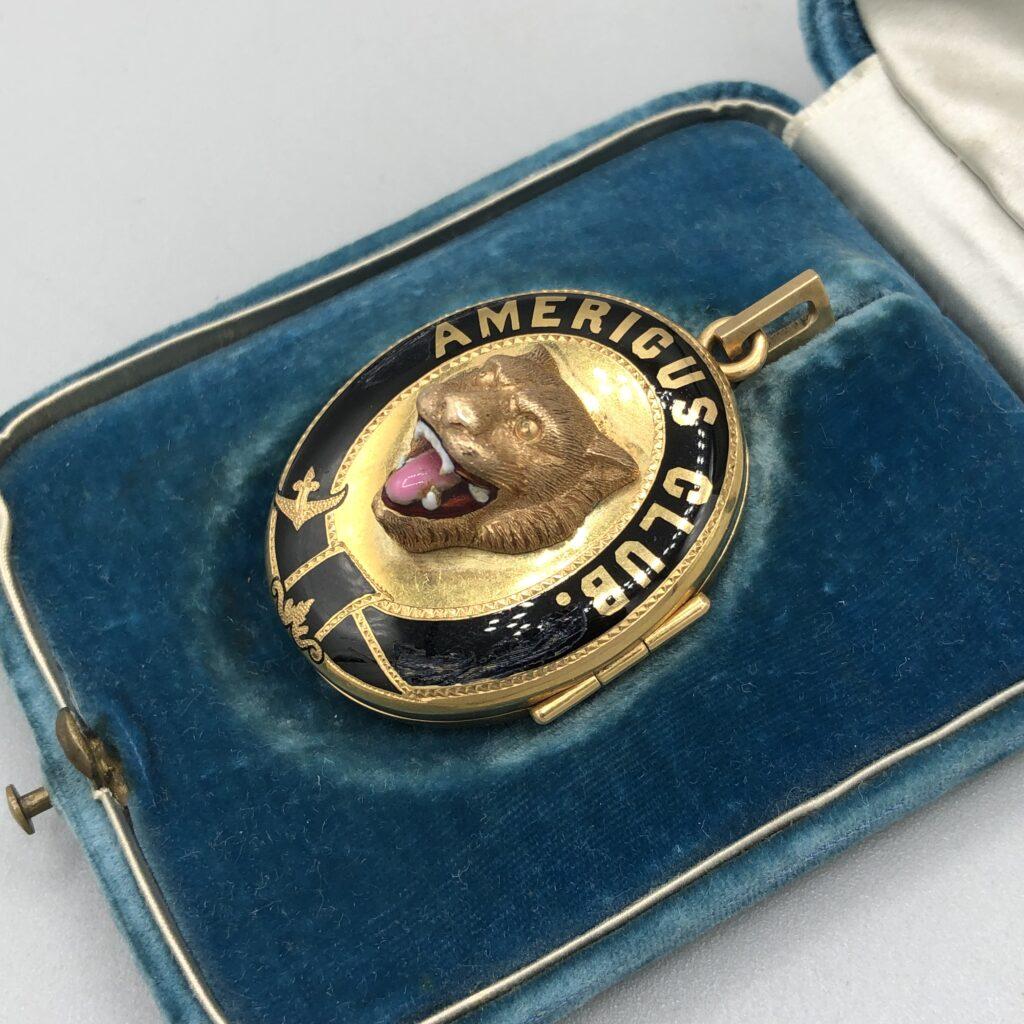

Boss Tweed’s Locket and Case (ca. 1860–1878)

For those of you who grew up in the New York Metropolitan area, or are at all familiar with political history, Boss Tweed is a name that will ring a bell. You may have seen any one of the hundreds of 19th century political cartoons or heard of Tammany Hall.

William Maeger Tweed (1823–1878), or Boss Tweed, was a corrupt New York City politician who moved his way through Congress, to Tammany Hall, before being elected to the bipartisan city board of supervisors, and holding multiple other offices and positions of power in the mid- to late-19th century.

He used his position to move his friends and acquaintances into other offices around the city (this became known as Tweed Ring), and stole funds from New York City estimated between $30 million and $200 million dollars.

This locket was a gift presented to Boss Tweed from an unknown individual. The piece is solid gold with a raised depiction of a roaring tiger on the front and “Americus Club” stretching across the top.

The inside opens to reveal a full color photograph of Tweed, the back has a raised monogram “WMT,” and engraved on the left side of the locket is “E.D. to W.M.T.” Before getting his start in politics, Tweed joined the volunteer firefighting company No.6 also known as Americus Engine Company, and the company symbol sported a bengal tiger.

Tweed would go on to adopt these two elements of his early life in his later social and political endeavors. The symbol of the tiger became associated with Tweed and Tammany Hall.

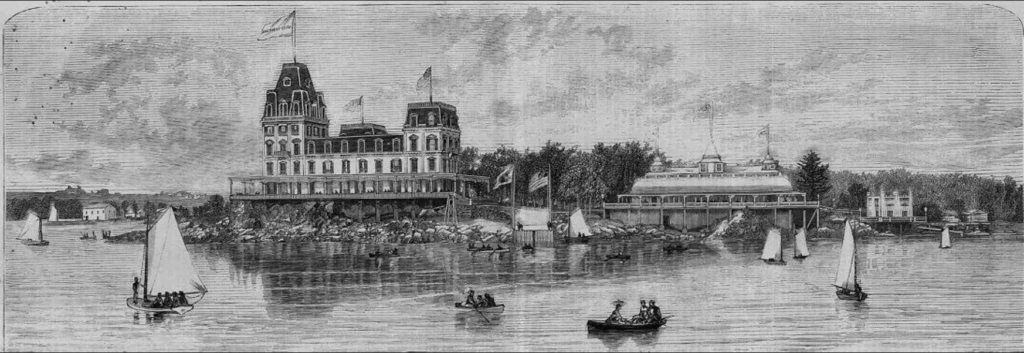

“Americus Yacht Club and Indian Harbor Hotel”, ca. 1873. Courtesy of the Greenwich Historical Society.

In 1860, Tweed constructed his first social club, The Americus Clubhouse, for him and his cortege in Greenwich Connecticut, this first clubhouse was modest and was eventually torn down to make way for an exuberant multi-story mansion named the “Americus Yacht Club and Indian Harbor Hotel” in 1971. Boss Tweed’s legacy has extended even into the present day, making this locket such an astounding piece of New York City history.

Horse Drawn Fire Wagon (late-19th–early-20th century)

Horse drawn fire wagons were quite the norm in U.S. cities up until the 1920s. This cast iron toy depicts a driver and their two horses racing towards a fire with the water pumper atop the back of their carriage.

Cast iron toys like this one were the fashion from the 1870s up until World War II due to the ease of production, affordability to a wide range of patrons, and their durability.

Production of cast iron toys declined during the Great Depression as few people could afford them and altogether stopped when the United States entered World War II, as metals like iron became critical to the war effort. Toys like this horse drawn fire wagon were not just play things but educational pieces, teaching children about the changing world around them.

This toy is particularly interesting as it reminds us of our ever evolving advances in safety and rescue procedures, something we all too often take for granted.

These fire horse squadrons were once valued members of their communities and responsible for the survival of people and structures ravaged by fires. These horses had to be extensively trained, from the moment the alarm bell rang they had to exit their stalls and get into position to be harnessed, once they were ready they had to gallop full speed ahead till they reached the flames, and stay on the scene for as long as they were needed.

The horses you see here are likely mid-weight horses that pulled the steamers or steam pumps. Lightweight horses would have pulled the hose carriage and heavyweight horses would have pulled the equipment, like ladders.

Retirement for these horses proved to be difficult. Oftentimes, after they resigned from the fire department, they were placed in less demanding jobs, such as pulling milk carts.

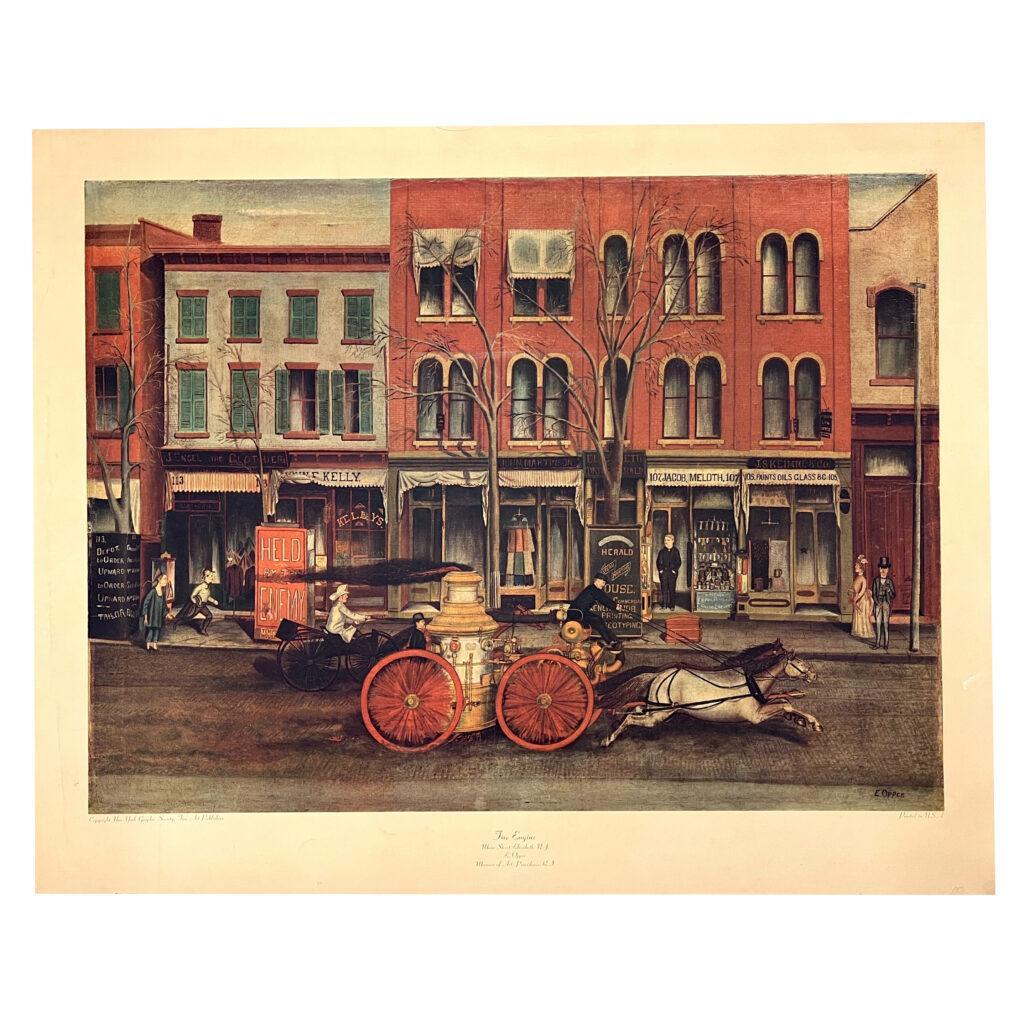

Edward Opper (1840-1940), “Fire-Engine on Broad Street, Elizabeth, New Jersey” ca. 1889. Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum 1991.070.0240

Even in their new roles, when the fire alarm would ring the horses would abandon their current post and rush to the scene like they had been trained to do all those years ago. This caused quite the stir as one milkman recalled his horse racing to the firehouse as the alarm rang, him and his cart in tow, leaving a trail of milk bottles and cans in the street.

Being able to examine and research these objects each day taught me new perspectives on history, as well as valuable collections care skills that I can use going forward as I continue down my path of art conservation and museum professions.

If you are interested in reading more about art and history I urge you to check out the other great blog articles the South Street Seaport Museum has posted (and some interesting continued readings I’ve attached as well). I hope you enjoyed reading about my experience interning at the Seaport Museum, and plan to visit the Corner of Curiosities when it will be open to the public!

Additional Readings and Resources

The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Europe by Oliver R. Impey, Arthur MacGregor. The Ashmolean Museum 1985.

“Kunst and Wunderkammern” by Georg Laue, Kunstkammer Georg Laue.

“Collecting for the Kunstkammer” by Wolfram Koeppe. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2002.

“British and French Prisoners of War, 1793-1815” Royal Museums Greenwich. November 2017.

“Boss Tweed Puts Greenwich on the Map” By Alan Owen Patterson. Connecticut Explored. Winter 2008-2009.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.